The website

A website is a collection of interlinked pages that share a unique domain name (e.g., google.com).

Each webpage in a website provides clear links—most often clickable text segments—that allow the user to move easily from one page to another.

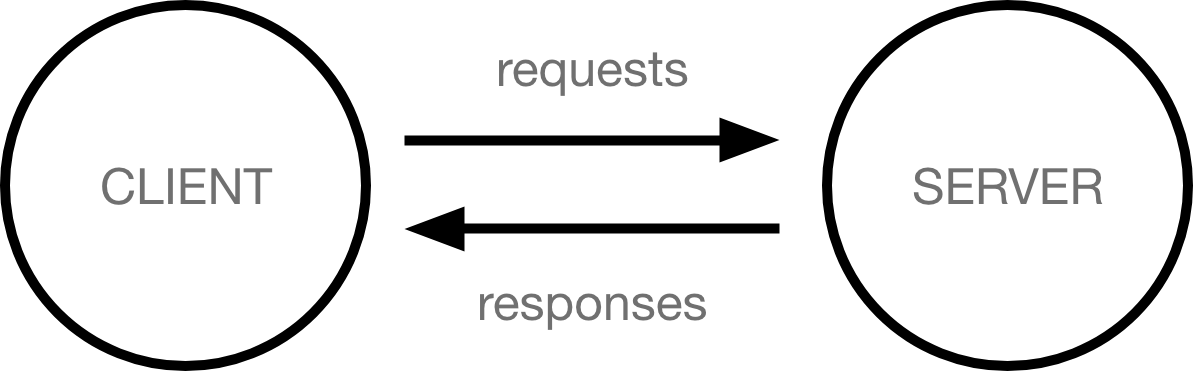

For a website to be accessible on the internet, the following 3 elements must exist (fig. 4.1):

- Domain name: the domain name, essentially the website’s unique address.

- A file system containing the information needed for pages to render in a browser (e.g., Chrome, Firefox), as well as the instructions for interacting with visitors.

- A server, consisting of the appropriate hardware and software.

The server provides the appropriate files and processes one or more requests from a client over the internet.

Clients can be a laptop, a desktop computer, or even a smartphone connected to the internet using a browser (e.g., Chrome, Firefox, Safari, etc.).

Figure 4.1: Schematic of communication between clients requesting files and a server responding with resources (source: developer.mozilla.org).

A good website should include the following characteristics:

- Be well-designed and functional, grounded in a clear goal (business).

- Be usable and quickly understandable to visitors.

- Be optimized for mobile devices.

- Contain fresh, high-quality, useful content.

- Display contact information in prominent locations.

- Provide clear cues for the next step, e.g., in buttons, forms, etc.

- Be optimized for search engines and the social web.

The basic building blocks of a website are the domain (address), the information it contains, and the structure for presenting that information.

Domain

A presence’s domain is essentially its digital address!

A domain name on the internet is a limited namespace within the global Domain Name System (DNS) assigned for exclusive use to a natural or legal person.

The domain name does not belong to the assignee as property; they have the exclusive right to use it for as long as registration fees are paid.

Domain names are, simply put, the unique, human-readable internet addresses of websites.

A domain can have various endings (top-level domains) such as .com, .eu, .gr, .net, .org, .info, .biz, .de, .it, .es, etc., depending on use and country of origin.

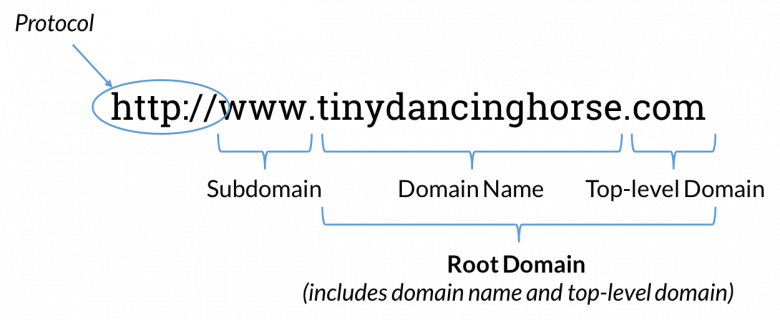

Figure 4.2: Parts of a domain name (source: kinsta.com)

More specifically, domains consist of three parts: a top-level domain (sometimes called an extension or TLD), a domain name (or IP address/domain name), and an optional subdomain.

“http://” is part of a page’s URL but not the domain name; it is known as the “protocol.”

Figure 4.3: Parts of a domain name (source: moz.com)

A domain can be purchased from official registrars; in Greece, examples include papaki.com, easy.gr, ip.gr, dnhost.gr, tophost.gr, etc.

With roughly 370 million domain registrations (2020), it’s clear one should choose a good domain for the online presence, as it will accompany the brand into the future.

Choosing the right domain is critical for success and it is extremely important to pick the best domain name from the start.

In general, a good domain should be short, easy to recall, easy to type, and easy to pronounce. These are valuable traits because the best advertising is word-of-mouth!

It is also very helpful if a domain can be associated with a story: humans remember and recall more easily and quickly something tied to a narrative.

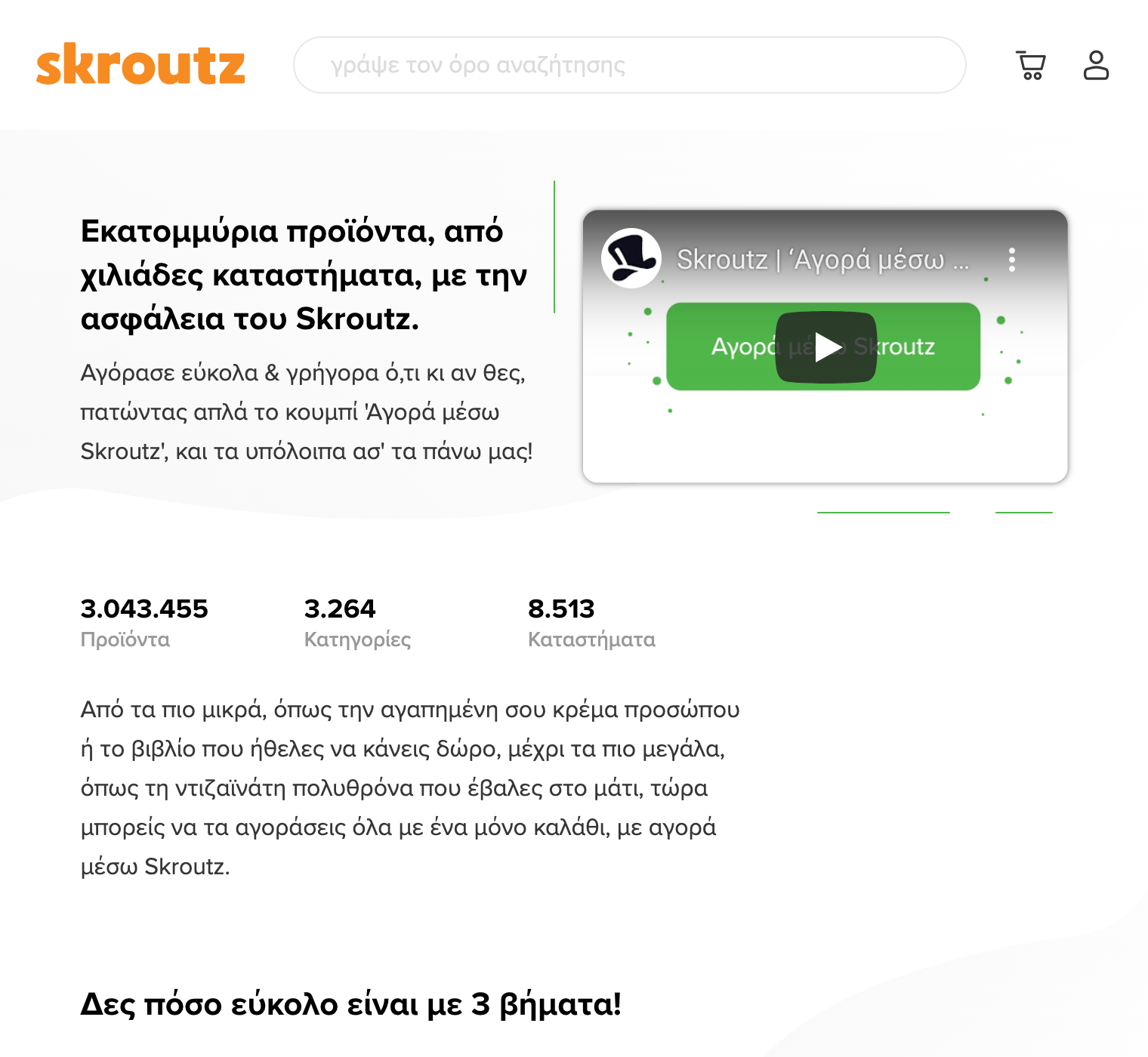

A favorite example here is Skroutz.gr.

A portion of Skroutz’s success is owed to its clever domain, which associates the Greek character “Skroutz” (a cheapskate) with price comparison and finding the lowest prices, as well as saving money: visit Skroutz once, see the logo and references across its pages, and it’s likely that for a future purchase it will come to mind quickly to find good prices and save money!

A domain is the first thing visitors will encounter, and is therefore very important: a poor choice can dampen interest and hinder success, while the opposite can happen with a smart choice.

While it’s not an exact science and there are no hard rules, there are several guidelines—echoed by Google—that can help:

- Length. Less is more. Short names are easier to remember and type, and thus more likely to be recalled and found. They also stand out more. It’s a good idea to keep domains within 2–3 words.

- Simplicity. People should be able to remember and type the domain quickly. Overly complex names and uncommon words can make recall or pronunciation difficult.

- Use keywords. Relevant keywords can help users identify a site’s topic from the search results themselves. Keywords might relate to a business’s focus, location, or even a call to action. The domain arahova-pansion.gr, for example, was chosen so the purpose (accommodation in Arachova) is immediately clear.

- Brand name. The domain name should reflect the brand and vice versa. Brands usually take time to build, so including the existing or prospective brand in the domain will help recognition. Obviously, never use someone else’s brand.

- Website name. Although obvious, the domain name should match the website’s name, or be as close as possible. Don’t confuse visitors who type or click a link with a given domain but land on a site with a different name.

- Good, not perfect. While picking a good domain matters, don’t delay launching the presence by chasing the perfect domain. A good-enough domain is fine.

- TLD choice. The most popular TLD is .com. It’s the first choice, especially for business. Country TLDs like .gr are equally good when most visitors will be from that country. Other TLDs can suit specific purposes (e.g., .net for networks, .org for organizations, .me for personal sites, .gov for government, .edu for education, etc.).

Things to avoid include numbers or hyphens (hard to dictate), words pronounced differently than spelled, old dormant domains used for something unrelated before, domains related to other brands or with negative connotations, etc.

A useful approach for domain ideas is to leverage Google Search and existing results for a given keyword.

For example, if building a site for recipes and suggestions, search some related terms and list domains that appear to inspire a new, available option. In such a case, results might include:

- tinamageirepso.gr

- coozina.gr

- mamapeinao.gr

- gastronomos.gr

- cooking-workshop.gr

- funkycook.gr

- xrysessyntages.com

- secretkitchenandtravel.gr

One could then combine parts of the above and/or original ideas to arrive at something available to purchase, such as CookingForLife.blog, myCooking.blog, 15MinutesCook.com, Syntages.online, CookLikeChef.com, SecretChef.com, OnlineChef.gr, etc.

With enough creativity, a memorable domain can be found.

Once found, mention it to a few close contacts and observe their reaction: do they understand what it’s about, and can they remember it after 2–3 days? If yes on both, the new domain is ready.

Essential information

Every website needs certain information and specific features, regardless of its type or size.

Whether it’s a single-page mini-site for an event or an eShop with thousands or millions of pages, some sections and elements are common to all websites.

A website is often the first touchpoint with a business or person, and that first impression must be positive.

Initially, there should be a clear, concise description of what the website is about—the nature of the online presence.

A popular book by Steve Krug on web user experience is titled “Don’t Make Me Think,” which is precisely the goal: a visitor’s first contact with a site should quickly communicate what it is and what it offers.

Ideally, within the first 2–3 seconds on a site, a visitor should understand where they are without effort or searching.

According to various studies (e.g., Time.com 2014), the average time spent on a website is no more than 15–20 seconds. This time is precious; it should not be spent figuring out where one is.

Typically, identity and purpose cues are at the top of the pages—the header.

In the header is the logo. The logo is the core and most important element of the site’s and brand’s identity. It’s the first thing visitors notice and recognize; it should represent the products, services, or overall presence. The logo usually links to the home page.

Often, below the logo is a short tagline reflecting the brand’s mission, e.g., Nike – just do it, Adidas – impossible is nothing, Apple – think different.

A second component concerns communication.

No one wants to make it hard for customers to get in touch. To avoid losing a prospective customer to a competitor, place contact options prominently.

Basic information is typically in the footer as well, including a link to a dedicated contact page with location/address (map), contact details like email and phone, a direct contact form, and often a live chat box.

A third critical component is the navigation section, enabling visitors to reach the sections they care about.

Navigation should be consistent across the site and reflect the information structure and main content pillars.

Figure 4.4: The logo, tagline, and primary navigation of arahova-pansion and the main content pillars (2021).

Once identity (logo, tagline) and navigation are clear, the next most important element is everything that contributes to achieving the site’s goal.

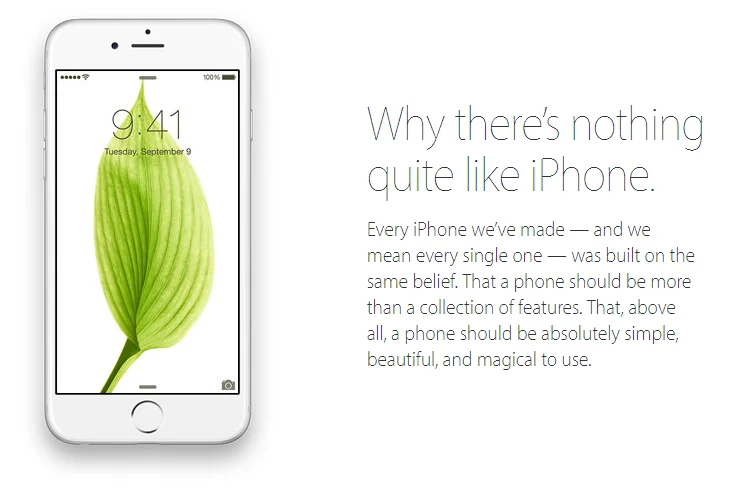

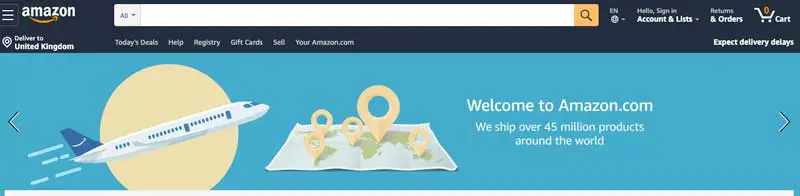

This varies by site type, but it’s very helpful to have a clear value proposition relative to competitors.

Prospective customers should know what differentiates the offering and why they should choose it.

The value of the online presence is the essence of all efforts: why the website exists and what its purpose is.

Value proposition elements can be a simple paragraph, short statements or a list of benefits/advantages, testimonials or reviews, a video, etc.

Figure 4.5: iPhone’s value proposition.

Figure 4.6: Amazon’s value proposition.

Figure 4.7: Netflix’s value proposition.

Figure 4.8: Skroutz Marketplace’s value proposition.

Beyond the value proposition, include all the elements and tools that convert the visitor into a customer. These cover all the content and functionality leading to conversion.

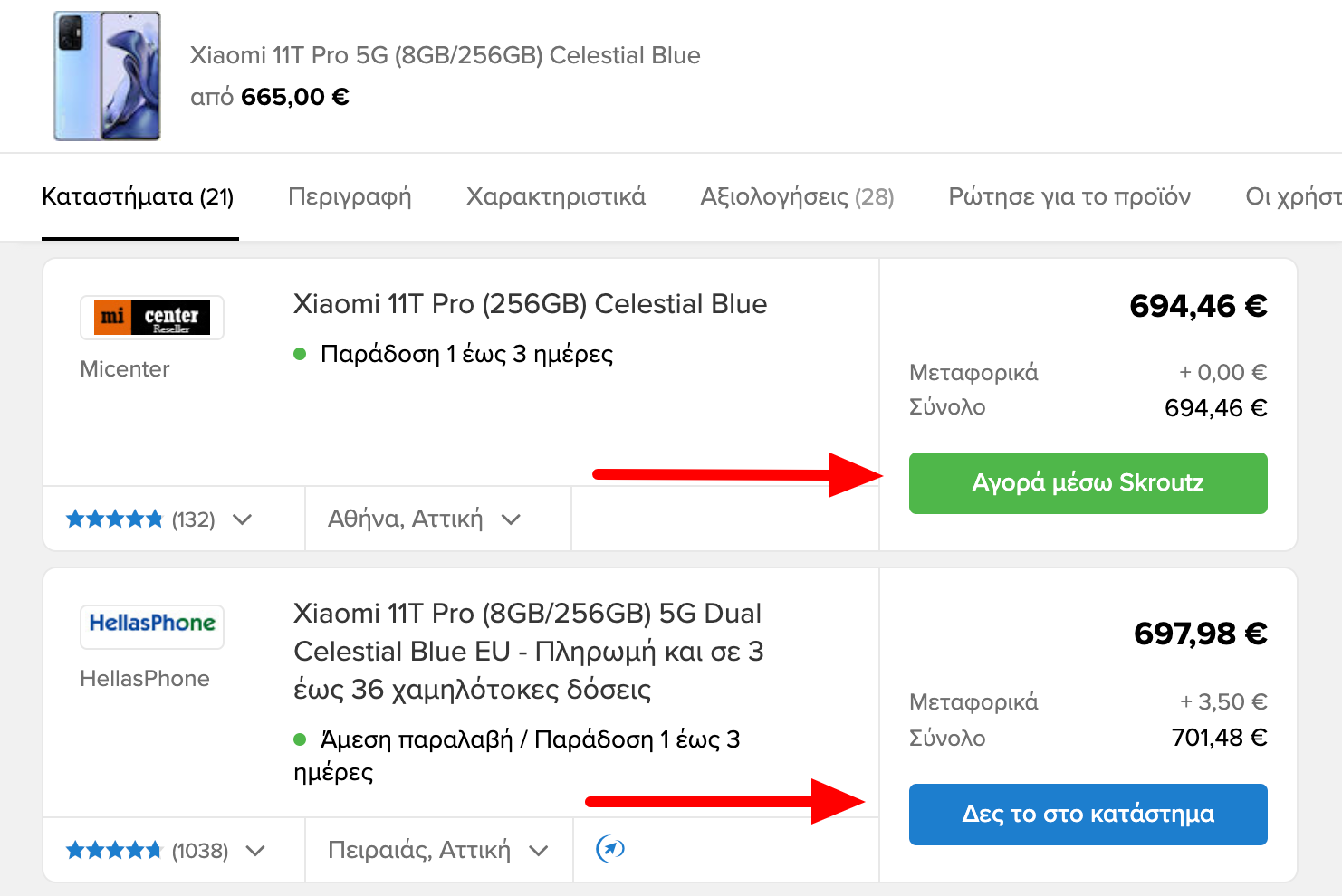

Usually, the last stop in this journey is a call-to-action button: for an eShop or marketplace, “Buy it”; for a hotel, “Book now”; for a mailing list, “Sign up,” etc.

Figure 4.9: Call-to-action buttons on Skroutz.

However, reaching the final button likely requires several steps.

For instance, to book a room, one might browse all available rooms, view many photos of a specific room, check availability for chosen dates via a calendar, see the price, and then hit “Book now.”

After that button, if there are follow-up steps like payment/checkout, the site should allow the visitor to pay.

All these steps—critical to converting a visitor—must be as user-friendly as possible, fast to execute, and provide clear feedback on interaction, success or failure, and the next step if any.

Regarding information needed to convert a visitor, it should be well-written, up-to-date, accurate, accompanied by supplementary media like images and videos, and provide everything needed to take the next step.

In a word, the information must be genuinely useful to the visitor.

Structure and depth of information differ by site: long-form blog posts, podcasts, videos, images, short text snippets in key spots—the goal is to answer the visitor’s question at the moment it arises.

An appealing logo with or without a tagline, proper navigation, a clear value proposition, fast and friendly functionality culminating in a call to action, and useful information with guidance to persuade the visitor to take the next step—these are the essentials of a website.

Two more elements, while not strictly necessary, greatly influence success: multimedia (videos, images) and user reviews.

As for video/multimedia, people today watch more video than ever. Cisco estimates that 82% of all internet traffic is video.

Users browse with shorter attention spans; videos and images let them consume information faster and more easily.

Whether a product, service, or initiative, images and videos let visitors see and get a feel for it.

With new video formats and platforms emerging (e.g., TikTok challenging YouTube among younger audiences), visitors are more likely to engage than with a plain paragraph or even a single image.

Videos also keep visitors longer, increasing the chances of conversion.

Videos primarily—and ample, quality images secondarily—are excellent ways to communicate with site visitors and increase the odds of success.

User recommendations and reviews are the second important, albeit not strictly required, element.

Research in eCommerce (Bigcommerce.com, 2021) shows that most people read online reviews before buying.

In fact, research suggests 91% of internet users read reviews and 84% trust them as much as a personal recommendation from a friend.

If the online presence—a product or service—has positive reviews from prior satisfied customers, more visitors will convert.

Negative reviews can be just as important if managed well.

Studies show 82% of review readers specifically look for negative ones, perhaps to see if anything important should dissuade them.

Though this sounds worrying, it simply means negative reviews draw increased attention and should not be left unmanaged.

Visitors will spend, on average, 5 times longer on the negative reviews, so a thoughtful response—or even addressing the issue, fixing it, and noting it on the website—can persuade future readers and possibly drive conversions.

Information structure

A site’s information structure is how its content and functionality are organized, and how different pages link to each other via internal links and hierarchy.

In short, interlinking and hierarchy.

It is how information is organized and presented (information architecture), so people and machines can navigate, read, and understand its content and operation.

A solid site structure facilitates easy navigation for both users and crawlers/bots, improving search engine rankings such as Google Search.

What is the right site structure?

It depends!

It varies by site type, size, and purpose.

The guiding principle is information architecture.

Good information architecture ensures a site’s content is organized, structured, effective, and consistent.

It’s neither easy nor simple to create an ideal site structure—no more than a layperson can draft architectural blueprints for a new house.

One might have ideas about room layout, where the living room, storage, bathrooms, entrance, and garage should be, but those are communicated to an engineer who then designs the best layout.

For very small or hobby sites, owners can DIY a structure; for more professional and larger presences, a professional—UX expert, designer, or experienced software engineer—should plan it.

To create a good information architecture, consider:

- User journey: Sites are built to serve visitors (in addition to their business purpose), so examine how visitors experience and interact with the site, and their expectations of how it should work.

A designer can define the user journey through interviews or a card-sorting exercise. - Content: Structure depends greatly on the type and volume of content.

An eCommerce site’s structure differs markedly from an academic site’s structure. - Context: Defined by business goals, cultural context, and available resources. All should be considered while structuring a new site.

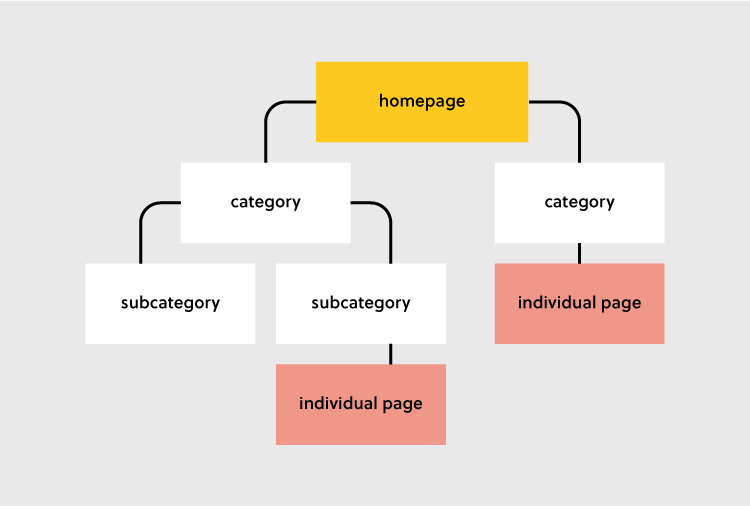

Whatever the site type and size, the general rule for sound hierarchy and structure is dividing all information and functionality into logical sections.

That is, a structure enabling a first-time visitor to successfully “guess” where to find the needed information.

Separating and hierarchizing the site into large, distinct sections with different information types is necessary.

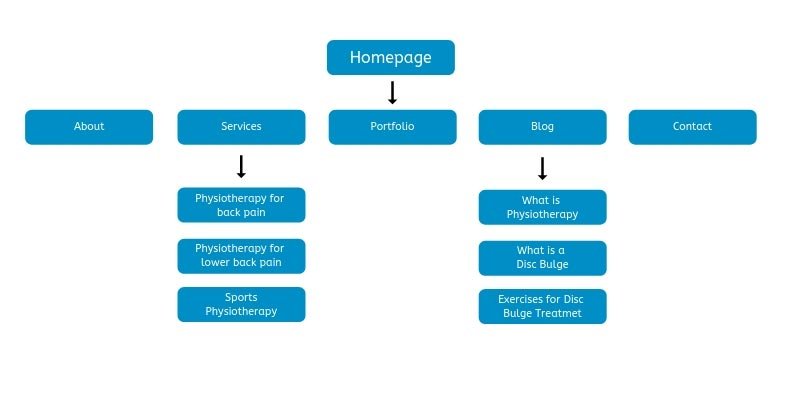

A simple, typical small-site structure would likely be (fig. 4.10): a home page with key information and links to main product/service/info categories, from which subcategories and product/service/info pages are linked.

Figure 4.10: Basic structure of a simple site (source: uxpin.com).

A business presence (fig. 4.11) might separate under the home page: About, Services, Portfolio/Case Studies, Blog/News, and Contact.

Figure 4.11: Basic structure of a simple business site (source: nomiscomwebdesign.eu).

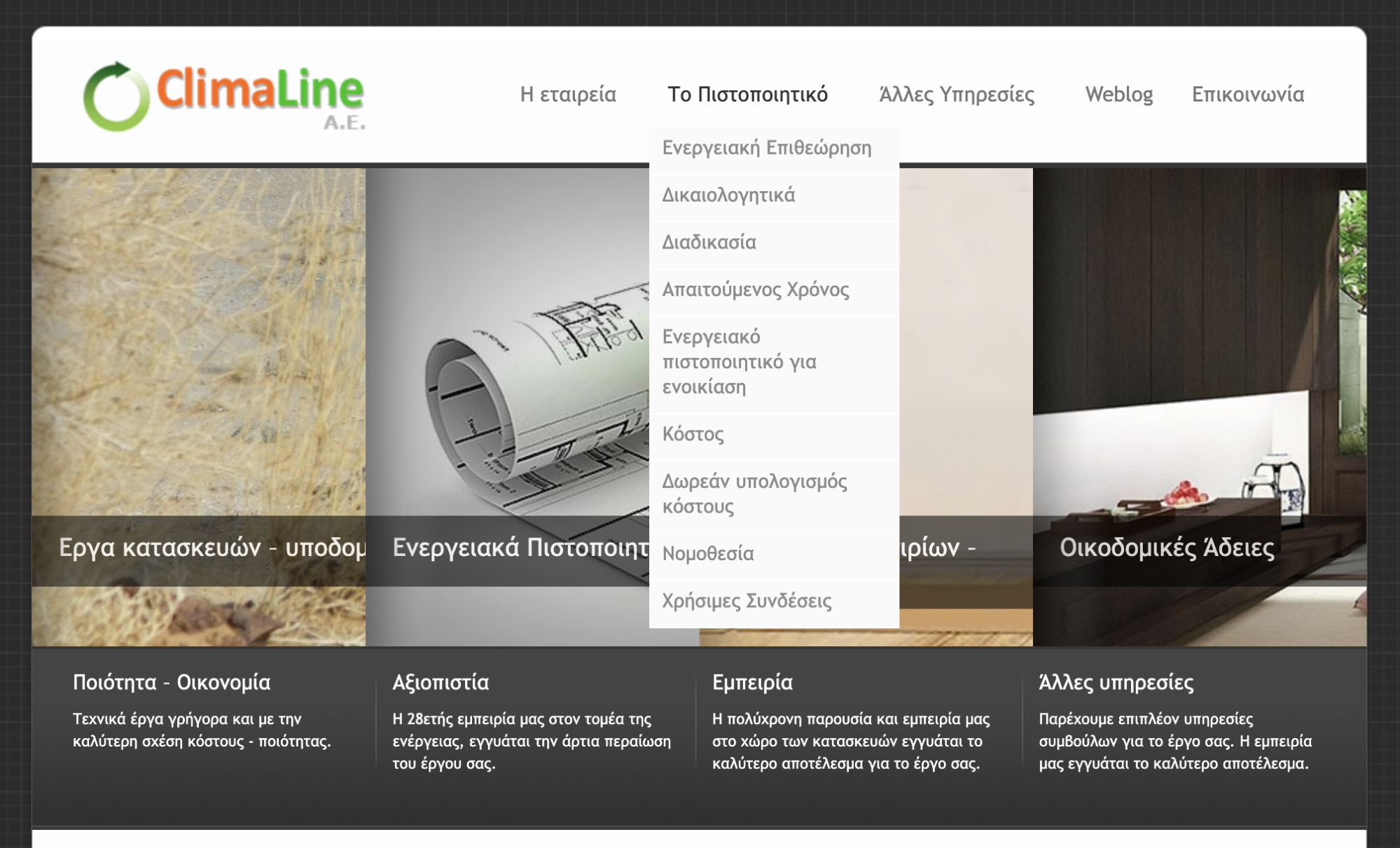

When building a site for an engineering/energy inspections and certification company, the structure was organized around: an About section (history, team, past projects), a dedicated section only for the Energy Certificate (including a free cost calculator and instant quote), a section for other services (permits, renovations, etc.), a Blog/News section, and a Contact page (fig. 4.12).

This was extremely important because most related sites then had merely a page among other services, while here there was a full-depth section—so the site quickly gained an audience and climbed into top Google rankings for relevant queries.

Figure 4.12: Content structure of an Energy Certificates services site (source: energiakoi.com).

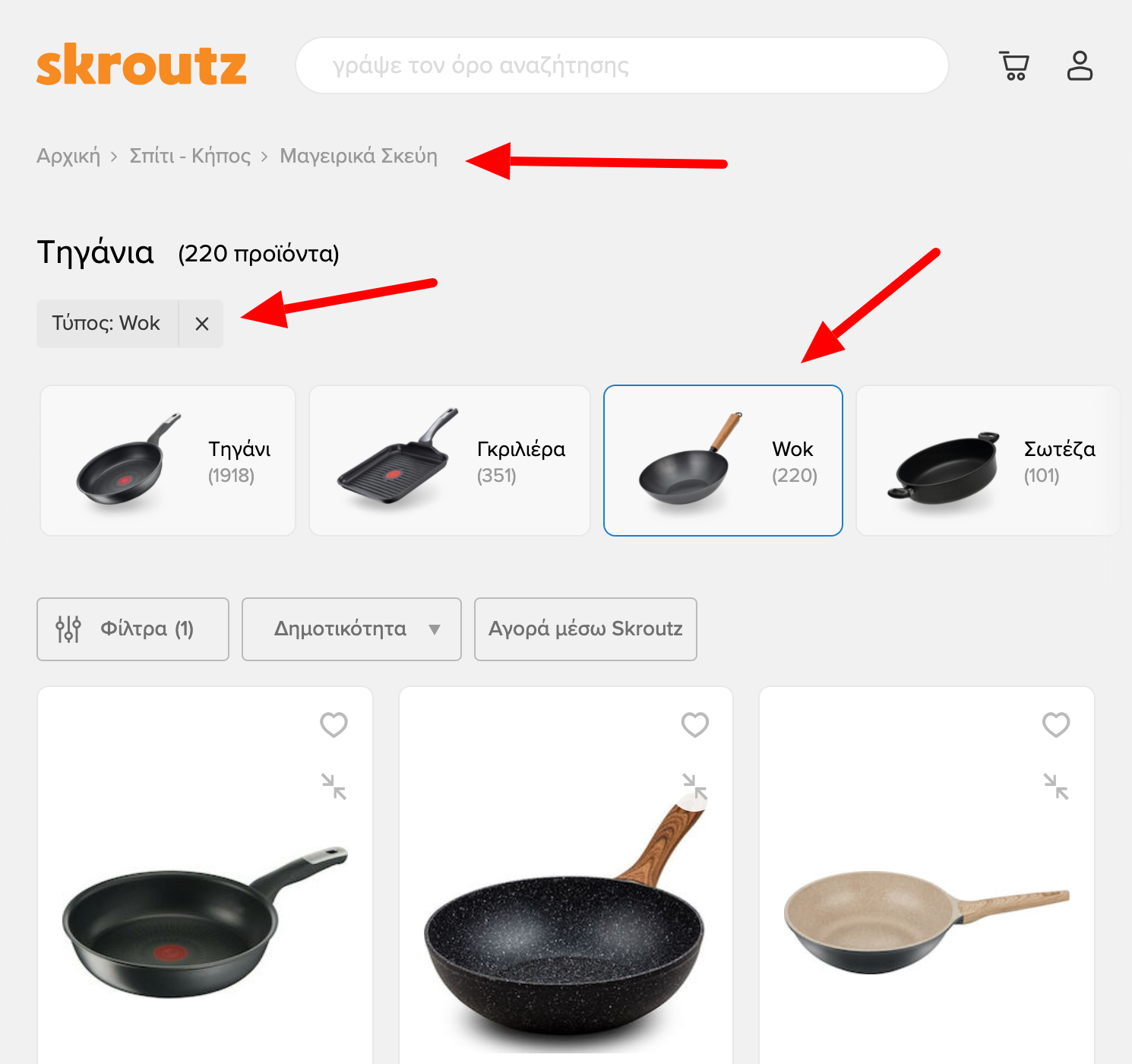

Beyond structure and navigation, other elements can help users understand where they are and the site’s hierarchy, and find information and sections easily.

These include breadcrumbs (a series of links reflecting the hierarchy), internal links and buttons/tags, in-text links, etc., as shown below (fig. 4.13).

Figure 4.13: Breadcrumb and filter navigation on Skroutz.gr.

While a site’s basic structure is best planned at the outset, it can change later as needs evolve or if something needs correction—or if an existing presence wasn’t structured properly initially.

Experience shows that more serious/professional presences that rely on their website tend to develop a sound structure over time, driven by visitor needs and business goals.

Investing effort upfront to build solid information architecture will help achieve better results in less time.

Technologies

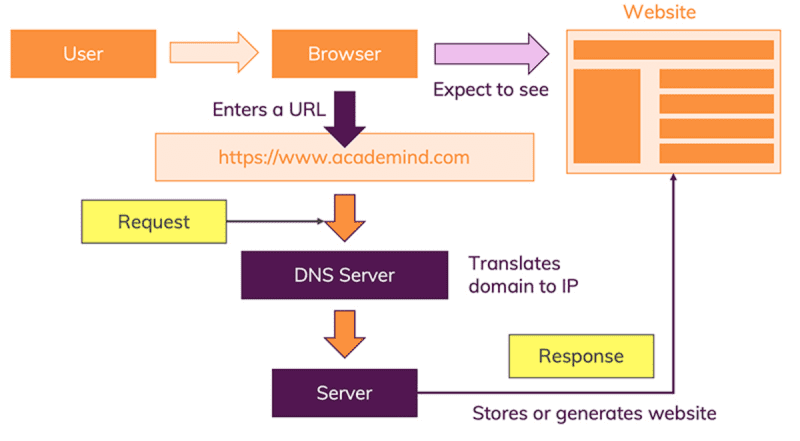

Every time a URL is typed into a browser, a series of background processes occur.

These processes culminate in rendering the page in the browser.

A URL (Uniform Resource Locator) denotes an address of a web resource. It is similar to a filename but includes the server’s address hosting the requested files and the protocol used for communication.

The entire process happens via resource requests and responses.

What exactly happens?

Typing a URL into a browser (e.g., Chrome, Firefox, Safari, etc.) is like going to a store: the browser queries a DNS server to find the actual server address for the requested site’s files.

That is, the store’s address is found first.

The browser then sends an HTTP request to the server, asking for a copy of the page—like a customer asking the store for certain products.

The server initially processes the request and, if approved, responds to the browser with “200 OK,” meaning “here you go.”

The server sends the response over the internet via TCP/IP (Transmission Control Protocol / Internet Protocol), a set of tools for communication.

A series of files required to present and operate the page are then sent to the browser—analogous to a clerk fetching the requested products from the back.

Finally, the browser receives the files and begins “building” the page, resulting in the information visible on screen (fig. 4.14).

Figure 4.14: How the Web works (source: academind.com).

Server.

A server is essentially a program that processes users’ network requests and serves files that make up webpages.

This exchange uses specific communication protocols (HTTP).

Basically, servers are computers used to store and deliver files needed for a website to function.

These files include text, images, video, fonts, stylesheets, scripts for functionality and interaction, etc.

A server can host many pages and multiple sites, and can serve thousands of users and requests simultaneously.

Most small and medium websites are hosted on rented servers for a fee over a specific period.

Costs depend on hosting type, duration, and storage capacity; a typical (2022) cost is about €10–20 per month.

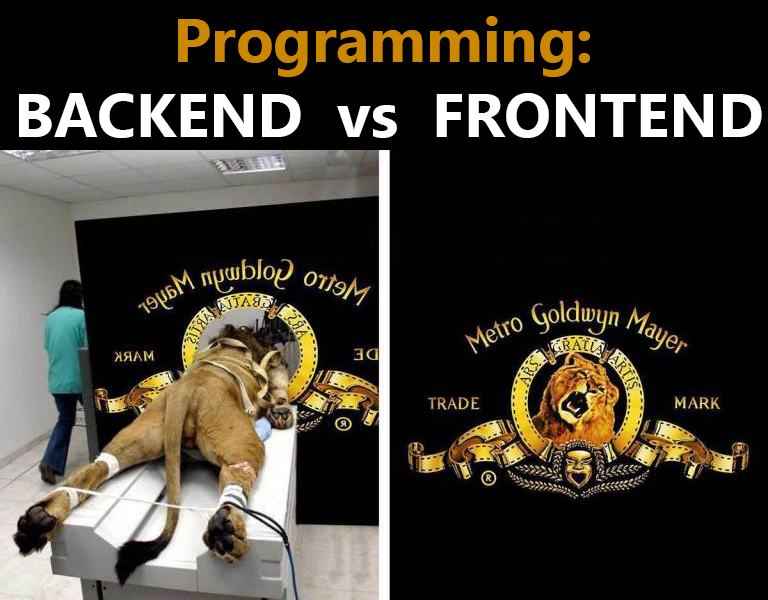

Website files are divided into two main parts: Backend and Frontend.

In simple terms, the Backend comprises files and technologies users don’t see or interact with, used to retrieve, create, and manage data in appropriate structures (databases).

The Frontend comprises files and technologies that deliver those data to the browser in a presentable form for users to consume and interact with (fig. 4.15).

Backend.

The backend relies on programming languages and frameworks to manage data on a server. By “manage,” we mean creating, reading, updating, and deleting data in a suitable data store (database).

Common backend languages include PHP, JavaScript (via Node.js), Python, Ruby, Java, Golang, C#, etc.

Frameworks often used include Laravel and WordPress (PHP), Express (Node.js/JavaScript), Django (Python), Ruby on Rails (Ruby), Spring and Hibernate (Java), and .NET (C#), etc.

Databases include PostgreSQL, MariaDB, MySQL, NoSQL options like MongoDB, etc.

Frontend.

The Frontend relies on languages and technologies that render a webpage and handle its functionality in a browser.

Core Frontend languages are HTML (the markup for a page’s information and text), CSS (the styling language: colors, layout, etc.), and JavaScript (the scripting language for interactions).

As in the Backend, toolchains exist for the Frontend, such as Ajax for asynchronous browser–server communication, SCSS for CSS, frameworks like Bootstrap and Tailwind, and JavaScript frameworks like ReactJS, VueJS, AngularJS, etc.

Figure 4.15: Frontend vs Backend (source: reddit.com).

Backend and Frontend work together to deliver a correct, successful experience, ultimately achieving business goals and converting visitors.

Content Management Systems (CMS).

Every site/page needs updates or edits to some degree.

Sites are either static or dynamic.

Static sites/pages have no management system; they are just HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and possibly images or videos. Changes require editing the final files on the server.

Dynamic sites have a management system and structure allowing content to be created, edited, updated, and deleted through an admin interface, without touching final files; the system generates those.

Recent years have seen a trend of building static sites—especially blogs—using tools or frameworks to generate them.

A static site can be very simple and suits simple needs, like an event, résumé, or announcement.

Most other needs are better served by a dynamic site.

Dynamic sites are based on a CMS—an application that lets one create, edit, and delete content without coding.

The most common CMS for many years has been WordPress, open-source software powering about 34% of all websites, with 60.8% share among CMSs.

WordPress powers 14.7% of the top sites worldwide.

Similar software includes Joomla and Drupal.

Using WordPress or similar for a website today is relatively easy; options include self-hosting on a private server or paying a company to handle proper setup and operation (e.g., Automattic, WordPress’s company).

CMSs like WordPress were built for users with little to no programming experience. After installation and initial configuration, managing the actual content (pages, images, texts, etc.) is simple and easy for almost anyone.

CMSs also support multi-user management.

Initial implementation of a website or CMS should obviously be done by someone who knows Backend and Frontend technologies, as well as CMS setup and maintenance.

This can be a freelancer or a company.

There’s no strictly right or wrong choice; both a competent individual and a specialized company can build a solid application.

Before commissioning an online presence, review prior work, ability to support ongoing maintenance, understanding of business needs, and costs for initial build and setup.

The key is having proper specifications and the business goal defined; from these, the right solution emerges—acceptable to both the owner and the implementer.

For Greek small-to-medium sites, a server located in Greece and choosing WordPress as CMS (or a similar framework) is a very good starting solution.

Regarding cost and time, it depends on what is being built.

A simple static page with a basic design might take a few hours and cost a few dozen euros. A WordPress site with basic information, a ready-made theme, and initial training might take several days and a few hundred euros. A bespoke CMS built from scratch with custom design and functionality would certainly take one or more months and several thousand euros.

Which is appropriate?

The view here is start simple, and only move to more customized/complex solutions when needs and business goals aren’t met.

This approach clarifies the workload of content management, each component’s contribution, the cost (time and money) of new functionality, and how users use and interact with the site.

Most importantly, it shows how well the owner can handle ongoing operations and management, the vision for the presence, and the knowledge gained from visitors via communication, etc.

A website is not cheap: it demands time, thought, energy, and money from the owner. The owner should recognize the presence’s value, limits, and role in the broader business.

As for the mountain-destination accommodation small business’s presence:

It was built six years ago on open-source WordPress.org with a free theme customized for readability (fonts) and layout, hosted on a Greek server.

Since then, it has served about 100,000 visitors per year successfully; aside from a design refresh planned to incorporate recent trends and keep it fresh, nothing else is planned regarding the infrastructure.

A similar solution was chosen to implement other comparable websites as well, though in some cases there was experimentation with alternatives.

Things to keep in mind:

- Choose a domain that is short, simple, and memorable.

- Ensure the first 15–20 seconds on the site convey what it is; within 2–3 seconds, visitors should know where they are.

- Design navigation and structure around clear content pillars and value.

- Plan for mobile-first performance and conversion-friendly flows from the outset.

Cover image source: Unsplash.com